Why We Love The Martian

On July 20, 1969, more than 600 million people watched as mankind landed a human on an extraterrestrial body for the first time in history. This moment galvanized an entire generation to study science, mathematics, and physics. It was a moment of unalloyed optimism in human progress and—more importantly—the vehicle of human progress, science. After Apollo 11 humans walked on the lunar surface five more times, already making space travel seem routine, and marking the beginning of a slow loss of interest in space travel. The awe that accompanied the first lunar landing slowly evaporated as developments in the aerospace industry over the next decades made space travel easier and easier, while our goals for space exploration became less and less ambitious. The moon landings gave way to the space shuttle, a vehicle whose relatively mundane missions were never publicized or followed in the way that The Apollo Program’s were. Then of course the Challenger and Columbia accidents made people question whether the scientific discoveries made possible by space shuttle missions were worth the inherent dangers. People became disillusioned with NASA. Out of this disillusionment has grown a perception that NASA takes public funds away from more pragmatic programs. It is popular to point out how many of the homeless could be fed for the cost of a single rocket launch, for instance. And among those that have stayed loyal to space exploration, a sense of frustration has grown around the ever waning budget of NASA. But with The Martian, it seems like those days of disillusionment are coming to an end.

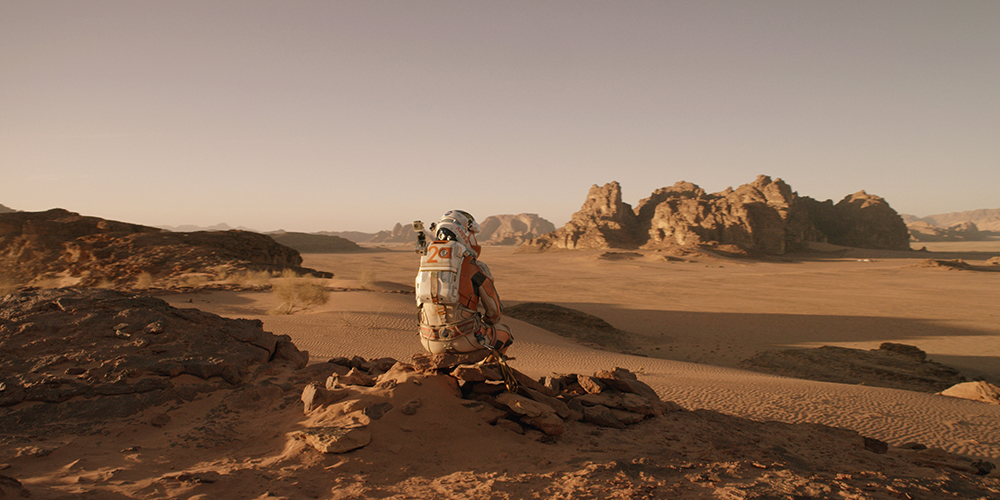

The Martian, taken by itself, is a very solid science fiction movie. It has a scrupulous approach to science that makes it one of the most believable science fiction movies I have ever seen—which is important, since it does not take place too much further in the future. It has an interesting cast of characters, none of whom seem superfluous. It has good performances from all actors and actresses involved. And it has a compelling story. But I think the film goes beyond these basic qualities. Watching this film left me with a feeling of complete contentment. It made me excited about the possibilities of a life devoted to the scientific. The Martian is all about what humans pushed to their limits can do with science. It depicts Mark Watney, a stranded astronaut using his wits and the technology around him to survive on a barren planet millions of miles away from Earth. It shows the collaboration of the people at JPL and NASA, as they figure out how to get Watney back home safe. It goes beyond showing the scientific achievements of one nation, encompassing humanity in its depiction of a China ready and willing to cooperate with the U.S. when NASA’s initial efforts fail. And it shows the impact of a single epiphany of genius, when Rich Purnell’s idea of gravity assistance allows for the ultimate rescue of Mark Watney.

It merits asking, when a mission to Mars may still be decades away, what role The Martian has to play in the alleviation of current disillusionment with the space program and space travel in general. This film marks a turning point—inasmuch as it reflects and influences the zeitgeist—where people are more idealistic and hopeful about space travel. It is films like these that can lead to a fundamental change in public opinion. A public that is excited about space exploration can lead to the political will that might send people to Mars. That is not to say that space exploration is still languishing. Private sector companies like SpaceX and Virgin Galactic are picking up the slack of the public sector. Recently SpaceX landed the first stage of its Falcon 9 rocket, a revolutionary development in rocketry that could make launching payloads much cheaper than ever before. To me and to everyone else at Holepop, The Martian represents a renewed sense of hope in the progression of the human race.